I can confirm that 5 flights in 4 days is not the best idea.

Especially when those flights are international:

Washington, DC -> Iceland -> Amsterdam -> Istanbul -> Abu Dhabi -> Nepal, where I’ve been living for 2 months. Naturally, my body spent the first week trying to make sense of the 10 different time zones it’d just flown through.

Nepal is the highest country on Earth - home to eight of the world’s ten tallest mountains, including Everest - earning it the nickname “The Roof of the World”.

More than 1300 peaks here soar well above 6000 meters.

…Let that sink in.

I’ve always been drawn to places that are a little bit rough around the edges and difficult to get to, and Nepal fits the bill. There’s only one international airport operating, and there aren’t any direct flights from The US or Europe... In fact, I learned from a taxi driver just the other day that the airport’s closed nightly through April 2025, which has driven the cost of tickets in and out of the country through the Roof.

I don’t fancy spending 30+ hours on a bus traveling overland into India, but I’m not keen on paying 3x the cost for airfare, either.

A problem for another day - I’m getting ahead of myself.

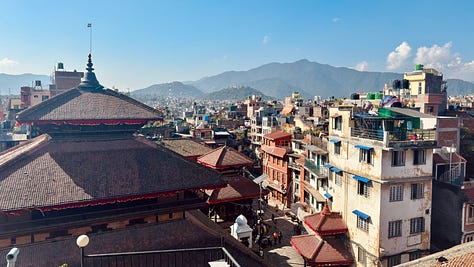

Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, is a stimulating swirl of culture and congestion. It’s one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the world, steeped in Hinduism and Buddhism, full of temples, art, and sculptures attesting to its rich history.

Kathmandu is just 200 kilometers from the city of Pokhara, which is much quieter by comparison. It’s a hotspot for adventure sports, the gateway to the snow-capped Annapurna Range, and where I’ve spent most of my time so far:

Despite the modest distance, the drive from Kathmandu to Pokhara takes 10+ hours because of the road conditions. Tourists pile into “VIP Sofa Buses” around 07:00am and join a wild procession of traffic that winds its way through the mountains.

I did the route twice in a week. I do not recommend you attempt the same. The way is so bumpy that it’s impossible to sleep, or work, or read, so you spend a lot of time looking out the window - or playing the bansuri, if you’re our bus attendant!

Past landslides scar the slopes. Steep drop-offs make sure that you’re never wanting for adrenaline. Of course, the drivers have done the route a million times, so I never got the impression that we were in any real danger. Still, it blows my mind that just one precariously-maintained artery connects two of the country’s most important cities.

Apparently, they’re constructing a new highway, but nobody knows when it’s opening. Same for the “international airport” being built in Pokhara.

Just the way I like it.

Nepal’s quite remote, but some areas are still surprisingly developed. For example, in Pokhara, a boatman ferried us across Phewa Lake:

We drifted past a Hindu temple on a tiny island, reached the other shore, disembarked, and picked up a path through the jungle.

Three snakes slithered out of the underbrush, startled. Insects as loud as a construction site screamed in our ears. After 45 minutes, the ascent opened up to a panoramic view of the city - and to my astonishment, it fucking sprawls:

Most tourists don’t leave the famous lakeside area, with its expedition outfitters, wool resellers, singing bowl suppliers, self-styled “Disneyland” theme park, bookstores and cafes and restaurants. But I’m lucky to have met Narayan, the man who guided me and my companion up into The Himalayas, toward Mardi Himal… More on that later!

Thanks to Narayan, I’ve had the opportunity to explore a bit more of the local life.

I’m thinking of one morning in particular. It began uneventfully enough.

I walked the road to The Juicery, one of my favorite cafes in Pokhara. I’d sorted breakfast and started to write for The Lighthouse when a text from Narayan came in, asking if I’d like to meet his family. Sure, I said, how about in a couple of days?

“Actually, in thirty minutes,” Narayan replied.

He explained that it was the fifth and final day of Tihar, a Hindu “festival of lights” that involves the celebration and worship of the four creatures associated with Yama, the god of death. Ah, I realized… So that’s why I’d seen dogs wandering around with tika on their foreheads and marigold garlands around their necks!

The fifth day of the festival, Narayan continued, was reserved for the celebration and worship of people. Traditionally, sisters place a seven-colored tika on their brothers’ foreheads to ward off the god of death for a year, and his family was keen to “adopt” me as their American brother so that I could receive the blessing.

But it had to happen in thirty minutes, because that was the astrologically-appointed time for the ceremony. Which is how I found myself on the back of Narayan’s motorbike, zipping through a maze of shopfronts, temples, and residences into what he called “the real Pokhara”, to reach his brother-in-law’s place.

I met his family. We shared a meal. And I’m happy to report that I received the seven-colored tika from my new Nepali sister:

“No problems from the god of death for you,” Narayan said.

…Which I took to mean it was safe to finally go paragliding.

As the sun set over lakeside, I found my way to Sunrise Paragliding, the pioneers of the sport in Nepal. I enjoyed a chat with Rajesh, the first Nepali paraglider in the country, who’s been at it for 28 years:

He noted the changing weather - “I’ve never seen it rain this late in the season” - and we talked about riding thermals thousands of meters in the air. “I love sharing my passion,” he said. “The possibilities here are limitless.” His eyes sparkled. “The other day, my friend launched near Mardi Himal and flew right over Fishtail.”

Fishtail - officially “Machapuchare”, sometimes referred to as “The Matterhorn of Nepal” - is a mountain just north of Pokhara, with a striking double summit that resembles the tail of a fish. It’s a sacred peak, believed to be home to the Hindu god Shiva, and it’s never been climbed to the top. Just imagine that… Soaring 7000 meters through the sky, looking down on an untouched holy mountain:

Granted, it wasn’t a bird’s-eye view - my first foray into paragliding took me high above Pokhara and deserves its own post! - but I did get a good look at Fishtail from the Mardi Himal viewpoint a few weeks back.

It took us five days to reach the viewpoint, beginning with a hike through terraced farmlands to the village of Ghandruk. I shared a campfire with Nepali tourists, who introduced me to Raksi, a strong but smooth drink made from kodo millet.

The next day, we covered more than 3000 meters in elevation… Down the mountainside, across a suspension bridge spanning the snow-fed Modi River, and up into lush rhododendron forests:

Rain fell. We pulled on our ponchos and pushed forward.

I listened to the sound of the rain pattering my hood, and it took me back to winter in New York City… The sound of ice pellets speckling trash bags on the curb.

There’s something soothing about hiking in the rain… I love it for the same reason I love rock climbing. It forces a complete focus of body and mind. You solve the problem in front of you, testing each step for purchase, shifting your weight, poking at the trail with your trekking poles. Mud, rock, stairs... So many stairs!

I’d expected to contend with the terrain directly, but instead, we spent much of our time climbing step after step after step. I learned that some parts of Nepal are so remote that such “roads” are the only way to get from Point A to Point B. Once, we passed a construction crew that was carrying materials for a new road... It would take them ten days to reach their destination, where they could begin their work.

We reached Forest Camp in the late afternoon:

It was a motley collection of teahouses offering overnight lodging, food, and - for a price - phone charging and gas-powered hot showers, made possible by donkeys packing in loads of fuel tanks and other supplies. We ate a dinner of “Dal Baht”, a lentil stew served with steamed rice. Other travelers sipped tea, traded stories in hushed tones, and played guitar. It felt like an outpost at the edge of the world.

It kind of was.

Eventually, we hung our clothes up to dry above the indoor fireplace and turned in.

The next couple of days saw us push onward to High Camp, scrambling over rocky trails and picking our way along exposed ridgelines, to the Mardi Himal viewpoint.

I’ve already written about taking Narayan’s death-defying shortcut up a slippery slope in the dark. It was a great adrenaline rush, and we were able to catch the sunrise.

We’d done it. We’d reached an elevation of 4200 meters.

Child’s play, by Himalayan standards!

After warming our hands and innards with masala tea at the viewpoint, we dipped beneath the clouds and descended through the mists, Low Camp-bound.

The trail was mostly deserted, but every now and then, we’d pass villagers transporting goods, porters balancing towers of bags on their backs, men herding donkeys, water buffalos, dogs shadowing us at a trot… They all came and went like ghosts, swimming in and out of the fog. Time fell away. I felt like I could go on forever.

In my experience, when you’ve unplugged on a trek for long enough, you reach a sort of tipping point. You accept the baseline discomfort of being on the road… The showers are infrequent, your clothes are in various states of neglect, there’s mold on the pillows, the leeches come for you in the rain, mosquitoes whine in the middle of the night... But fuck it. There’s almost something comforting in it, really.

You don’t want to return to civilization.

You want to see how much further you can push. You want to find your limits. You want to feel your heart beating in your chest reminding you you’re alive.

We made it down to Siding Village, right before a storm tore through the mountains. Narayan spoke with some of the locals there. “The farmers are worried,” he said. “They hope the rains don’t wash away the rice harvest.”

There weren’t enough Jeeps to go around in the wake of the storm, so we split the ride back to Pokhara with a Nepali family we’d met in the rhododendron forests.

I was grateful for the four-wheel drive… The rain had washed away the road in places, and waterfalls fed into surging streams that plunged off the mountainside:

We slipped and slid dangerously close to the edge, many times:

After a couple of hours, the city bled into the countryside. Traffic picked up. Pollution - much worse than I’d expected in The Himalayas; in fact, it drops the average life expectancy of Nepalis by 3.4 years - scratched at my lungs. And I thought a thought I’ve thought many times: How do you come back from an experience like this?

How do you go back to your life knowing that all of that beauty is out there? The absurdity of the rat race hit me… The social constructions and conventions that keep us quietly humming along, on the beaten track more often than off of it.

50 million years ago, epochs before Homo sapiens emerged, the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates collided, birthing the Annapurna Range.

From my guesthouse in the south of Lakeside - if I climb all the way up to the roof, on a clear day - I can see it soaring 8000 meters skyward, high above the traffic and pollution, like an exclamation point waiting to finish our species’ sentence.

The Roof of the World.

Sounds amazing! But that bus trip? Ooof, no way!

man the light on Machapuchare was awesome! and shit that bus ride looks wild! Hell of a story though. Are you going to be in Nepal for a bit?