What if we’re making things worse?

DUNE: PART TWO immerses you in its world - and then asks if you should be there in the first place

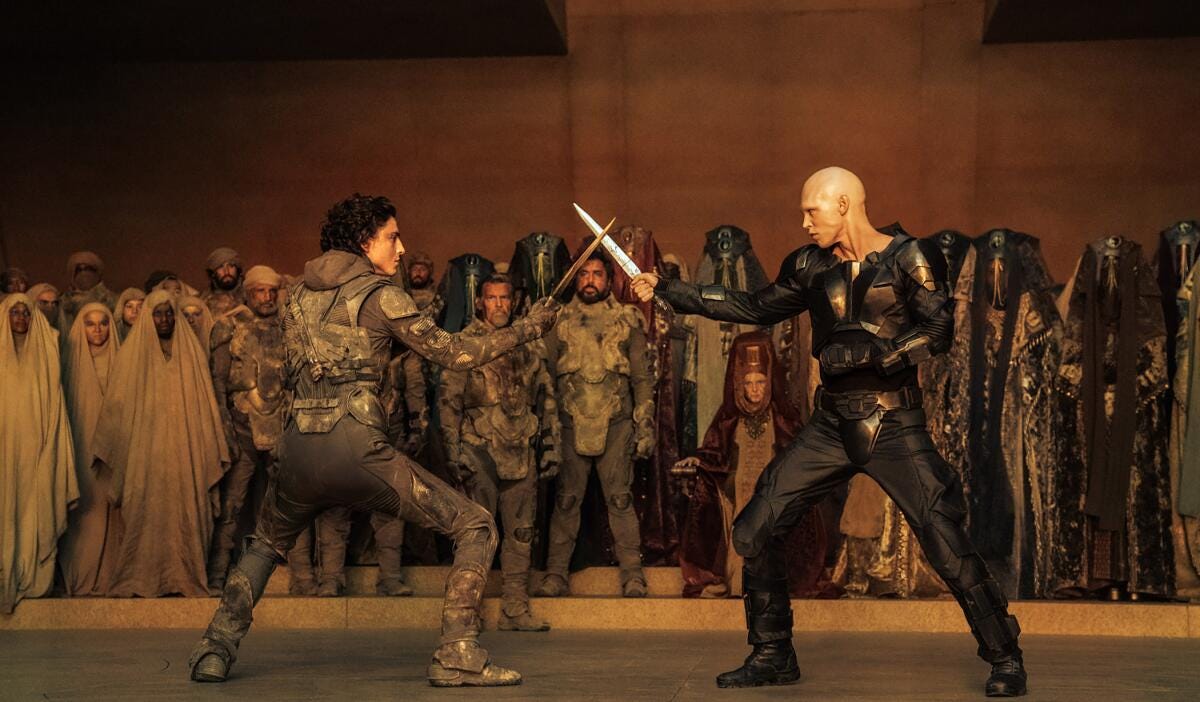

There’s a scene early in Dune: Part Two where Paul Atreides celebrates a successful guerrilla attack on a spice harvester in the desert. He’s cheered by hardened Fremen warriors - the people who call Arrakis home, there long before the colonists arrived to exploit the planet - all of them impressed by Paul’s preternatural fighting ability.

Paul, himself an outsider, uses the moment to propose a reinvigorated alliance against the reigning foreign power “so that this planet can be yours once more” - and also so that he can avenge the massacre of his family.

Stirred by Paul’s commitment to winning their freedom, the Fremen call for him to be made “Fedaykin”, ushering him into their inner circle.

“He needs names!” the Fedaykin insist enthusiastically.

And so Paul adopts the war name “Paul Muad’Dib Usul“, which means “the base of the pillar who points the way”, connoting strength, wisdom, and leadership.

As a result, he is welcomed as their brother and treated as one of them.

[Spoiler alert] Ultimately, Paul’s acceptance proves disastrous for the Fremen.

He uses them to achieve his own ends at great cost. Of course, it’s not that simple - Paul doesn’t want to play the role of messiah and risk starting a mass genocide, nor does he want to lose Chani, the Fremen warrior with whom he’s in love - but he sees only “a narrow way through” to ensure the survival of his family’s legacy.

And so, in director Denis Villeneuve’s words, Paul “becomes what he was trying to fight against”. It’s not your usual Hollywood story.

In many ways, given its bold craft and thematic complexity, Dune: Part Two feels more like an arthouse film than a traditional blockbuster. That’s why it’s disappointing to see it largely overlooked during this year’s awards season - especially since Part One received more recognition, despite primarily serving as setup for Part Two.

For example, Villeneuve didn’t receive an Oscar nomination for Best Director, which blows my mind. Adding insult to injury, the film’s score was ruled ineligible for surpassing the Academy’s limit on preexisting music - a real shame because I think it may be Hans Zimmer’s best work yet. Just look at the artistry on display!

Still, Dune: Part Two earned five nominations - half as many as Part One earned - including for Best Picture, Cinematography, and Sound.

I have this theory that you need to see a great film at least three times in order to fully appreciate it. The first time, you watch to experience it. The second time, you watch to analyze it. And the third time, you watch to understand it.

That third viewing is where heart and mind come together, when intuition and analysis integrate so as to reveal to you precisely how the film is casting its spell.

But for Dune: Part Two, I needed a fourth viewing in order to reach out and pluck that sense of integration from the ether.

I found it when I noticed how camera focus tracks the characters, not the spectacle, while explosions erupt behind them.

I found it when I realized I was watching an Extreme Closeup of Chani’s eyes filling a five-story IMAX screen.

And I found it in the film’s quieter, more contemplative moments - in how they intentionally hold space for the character of Arrakis to move us with its harsh, startling beauty. The sound of sand drifting across the landscape, the sight of spice glittering in the sun… There is time for wonder, for awe, two vital but elusive emotions.

In other words, Dune: Part Two engulfs you.

Yet despite the film’s impressive scale, it’s a surprisingly intimate experience that places people (and the planet) at its center, painted on the largest conceivable canvas. It’s relentlessly sensory, in a way that few modern films are.

The last film I remember locating me so squarely “in my body” was Alejandro Iñárritu’s The Revenant. I felt like I could feel the wind and smell the mud... Shiver at the touch of freezing water and bask in the warmth of a flickering fire.

No wonder Dune: Part Two landed nominations for cinematography and sound. They’re the elements of style that govern what we see and hear - the senses to which film has direct access - collaborating with performance, production design, and other departments to indirectly evoke all of our senses, creating a feeling of full immersion.

Villeneuve plans for immersion from the very beginning.

After writing the screenplay, he storyboards the film. Then after storyboarding, he rewrites the screenplay. “Storyboards supersede the screenplay,” he explained at Lincoln Center in New York City while discussing his creative process. “And nature supersedes the storyboard, meaning that when we go on set, if something happens with the actors or with the light, or with a natural event that feels absolutely inspiring, I will just throw the storyboards over my shoulder and improvise.”

He also mentions incorporating sound ideas into the screenplay, so that sound is embedded into the structure of the movie early on.

By proactively leveraging sight and sound in his creative process, Villeneuve taps into the unique language and power of cinema. He’s not leaning on dialogue or haphazardly shooting coverage to figure out messily in the edit; on the contrary, there is tremendous care and creative intent poured into every frame from the beginning.

That same level of thought calibrates the film’s thematic treatment.

Far from being an abstract sci-fi with no relevance to the present, Dune: Part Two feels like a timely warning. It’s one of my favorite films, partly because it connects so deeply to my own experiences and observations. Paul, an outsider, steps into a cause he believes in, only to watch his intervention spiral into unintended consequences.

It’s a common problem with social action - for example, when people volunteer for a nonprofit abroad, go on a missions trip, or otherwise contribute to a cause that falls far outside their own purview.

Let’s give people the benefit of the doubt and assume that many such attempts to address suffering and injustice are well-intentioned. But well-intentioned actions can be misguided. What’s interesting to me is how they sometimes complicate the very problems they seek to solve, whether through some sort of misunderstanding, miscalculation, or moral failure.

It’s been a few years, so I’m probably forgetting some of the details, but while living in Southeast Asia, I heard about a nonprofit that was excited to “upgrade” houses in the jungle. What they saw were structures vulnerable to the rain, so they poured considerable time and money into replacing thatched roofs with tin.

The villagers made a show of thanking them. But when the aid workers left, they removed the tin and put the thatching back the same as before.

Why?

Because the tin turned the houses into proverbial ovens during burning season, and a little bit of rain was preferable to unbearable heat.

Instead of listening to and working with the villagers to determine their needs, the (well-intentioned) nonprofit dictated from the top down, implicitly assuming that they knew better than the people who lived there. The villagers didn’t share their knowledge because they didn’t want to appear ungrateful or risk offense.

Such miscommunication can be avoided, but in my travels, I’ve heard countless different versions of this same story, and they’re merely the tip of the iceberg.

Growing up a missionary kid in Uganda - where my friends were the kids of diplomats, military officers, and NGO workers - I saw firsthand how religion, politics, defense, charity, etc. can carry with them the assumption of cultural superiority, like a virus in a computer program.

I’ve tagged along on international high school missions trips that cost more to run than they give back to the communities they claim to help.

I’ve watched aid workers fight over turf in literal war zones so that they can justify the scale of their influence to their supporters.

But what most stays with me, what most makes me question the efficacy of some forms of social action, is my own lived experience of a rather “Paul Atreides” story.

In short, I found myself welcomed by people resisting a colonizing power. I was ushered into their inner circle; given a “war name” (“The White Bird”, because of my long legs and skin color); welcomed as their brother and treated as one of them. But I began to wonder if I was party to some of the very things I’d meant to stand against - and if by involving myself, I was creating more problems than I was solving.

We’re all products of our experiences, and I’m acutely aware of how my own have tinged my worldview with a cynicism against which I struggle everyday.

I want to believe that it’s primarily a question of HOW we work toward a better world, not IF… That it can be responsible to try and affect change and indeed is possible to do so. If we work to mitigate miscommunication, if we keep our egos and assumptions in check, if we hold ourselves morally accountable and guard against serving our own agendas (subconscious or otherwise)…

Then maybe, MAYBE we stand a chance.

Here I’m reminded of Tree of Smoke, by Denis Johnson, one of my favorite writers. It’s a book about the Vietnam War.

The final pages belong to the character of Kathy, a Seventh-Day Adventist and aid worker who carries the weight of much of the book’s considerable grief. I know that weight. I’ve carried it myself - the gnawing realization that good intentions aren’t nearly enough in a world that sometimes seems beyond saving.

As Kathy reflects:

The scene before her flattened, lost one of its dimensions, and the noise dribbled irrelevantly down its face. Something was coming. This moment, this very experience of it, seemed only the thinnest gauze.

She sat in the audience thinking - someone here has cancer, someone has a broken heart, someone's soul is lost, someone feels naked and foreign, thinks they once knew the way but can't remember the way, feels stripped of armor and alone, there are people in this audience with broken bones, others whose bones will break sooner or later, people who've ruined their health, worshipped their own lives, spat on their dreams, turned their backs on their true beliefs, yes, yes, and all will be saved. All will be saved. All will be saved.

A while back, I met a woman working with a nonprofit to build a post-conflict society in Israel and Palestine. I asked her how she stays positive. “It’s sort of like a blues mentality,” she said. “Understanding the full weight of history and reality and the million reasons not to be hopeful, and still maintaining that hope.”

“How do you do that?” I asked. “Why?” She thought about it. Shook her head incredulously, shrugged, and met my eyes:

“Because you have to. Resistance is the highest form of love.”

So many wonderful thoughts to ruminate on in this piece Michael. I too loved Dune Part II. It’s one of the few films I went back to the theater twice to see. Currently rereading Dune too and looking forward to my third viewing of the films soon.

That was such a lovely read!